1. Who is most at risk of climate anxiety?

- Children, youth and young adults

- Scientists and climate activists

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

(Source: Climate Mental Health Network)

How Do You Deal with Climate Anxiety?

2. Climate emotions glossary

Some terminologies related to climate emotions are well known and used, while other terms are developing as we continue to understand the climate emergency and the social and emotional impacts that arise from it. This section provides a short overview of currently used terminologies related to Climate Emotions.

“Climate change is a future problem. But it is also a past problem and a present problem. It is better thought of as a developing process of long-term deterioration, called by some psychologists a “creeping problem.” The lack of a definite beginning, end, or deadline requires that we create our own timeline. Not surprisingly, we do so in ways that remove the compulsion to act. We allow just enough history to make it seem familiar but not enough to create a responsibility for our past emissions. We make it just current enough to accept that we need to do something about it but put it just too far in the future to require immediate action”

(Marshall 2015 in Hayes et al. 2018)

Eco-grief

Ecological Grief is:

“the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change”

Solastalgia

The term ‘solastalgia’ was developed in 2005 by Glenn Albrecht, an environmental philosopher, to name the growing phenomenon of the distress that people experience who live in environments with extreme transformation (T. Tupou et al., 2023).

“Solastalgia is the pain or sickness caused by the loss or lack of solace and the sense of isolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory.”

Especially the well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, who are connected to the environment through place, identity and culture and are impacted by such changes.

Climate anxiety and eco-anxiety

Climate Anxiety and Eco Anxiety refer to feelings of distress, fear, and helplessness stemming from concerns about the environmental crisis and its impact on the planet’s ecosystems and future generations. Climate Anxiety is an ongoing or chronic fear of environmental doom and can apply to past, present or future events.

Eco-anger

Eco-anger represents the emotional response characterised by frustration, resentment, and outrage towards individuals, institutions, or systems perceived as responsible for environmental degradation and climate change.

Eco-depression

Eco-depression denotes a state of profound sadness, hopelessness, and despair triggered by the destruction of natural habitats, species extinction, and the looming threat of ecological collapse.

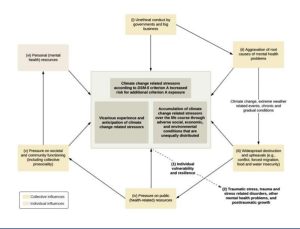

Psychosocial hazards of climate change

Psychosocial Hazards of Climate Change encompass a range of adverse mental health effects resulting from exposure to climate-related stressors, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and increased risk of suicide, exacerbated by environmental disasters and socio-economic inequalities.

Climate load

Climate load refers to the cumulative psychological burden borne by individuals and communities due to prolonged exposure to climate change-induced stressors, including extreme weather events, environmental degradation, and uncertainty about the future, leading to emotional exhaustion, burnout, and diminished resilience.

Climate denial

Denial is when you really want something not to be true. Climate denial is the refusal to accept the scientific consensus that climate change is happening and that human activities, like burning fossil fuels and deforestation, are the main causes. This can involve rejecting the fact that the climate is changing, denying the role of human actions, downplaying the potential impacts, or believing in conspiracy theories that claim climate change is a hoax. Climate denial often leads to misinformation and delays in taking action to address the serious risks posed by climate change. If you are in denial, you’re trying to protect yourself by not accepting the truth about something happening in your life. Denial can help you cope with difficult situations for a while, but if you stay in denial too long, it can stop you from getting help or dealing with problems. In the short term, denial can be helpful, giving you time to get used to tough situations or learn new things. But if it goes on too long, it can become harmful, making you look for false information that supports what you want to believe rather than what is true (Source: The Climate Reality Project).

3. Understanding your emotions & safe engagement with climate change and climate justice

(resource for individuals)

Also visit: Safe Engagement with Climate Justice and this toolkit

Engaging with climate change and climate justice can feel overwhelming, but it’s important to take steps that are safe and manageable. This guide will help you understand how to get involved as an individual, focusing on actions you can take to make a positive impact while protecting your own well-being. Whether you’re just starting to learn about climate issues or looking for new ways to contribute, this guide will provide practical advice and support for your journey.

“No need to give a PowerPoint about CO2 levels. Talk about how it feels to be living at this time. Talk about what you think the future holds. Talk about your fear, dread, rage, grief and everything else. This contributes to transformative change; it helps us collectively wake up from the trance of denial.”

(Margaret Klein Salamon, Psychologist)

Community Resources for Climate Emotions presented by Psychology for a Safe Climate invites you to explore distress, grief, hope, determination, powerlessness, anger, awe, despair, loneliness, and fear… by exploring “connecting with self, feeling with others and shaping our future.

3.1 Trauma and vicarious trauma

Trauma

Trauma, which originally meant a physical wound, also refers to emotional harm caused by distressing experiences. The American Psychological Association describes trauma as any event that brings intense fear, helplessness, or confusion, leaving a long-lasting negative impact on a person’s emotions and behaviour. Climate change, caused by human activity, is making traumatic events like severe storms, floods and droughts more common. These events not only cause physical damage but also emotional distress, such as losing loved ones or homes. Ongoing climate impacts, like forced migration and conflicts over resources, can lead to chronic trauma. Denial of climate change can be seen as a way of mentally coping with overwhelming stress, showing the need for more awareness and collective action.

(Source: Process Linking Climate Change and Trauma)

Ecopsychepedia lists common symptoms, unequal experiences, research findings and some suggestions on what can be done to address climate trauma.

We Need a Climate Movement that Addresses the Trauma of Fighting for a Burning Planet. The Commons – Social Change Library

Also, see The Four Trauma Responses in a Movement Context and The Commons Social Change Library.

and

Vicarious trauma

Vicarious trauma happens when we are indirectly exposed to someone else’s trauma, and it affects our mental health in a similar way to going through the trauma ourselves. This stress can take a toll on our mental well-being and impact many parts of our lives. Building resilience, whether in your organisation, community, or family, can help protect and manage mental health. Phoenix Australia provides a helpful guide to developing healthy habits that can reduce the impact of vicarious trauma.

Read more: Vicarious Trauma, Phoenix Australia

3.2 Climate emotions well-being tips

A. Quick tips to deal with climate anxiety

- Take Action

- Take breaks from Climate Content Inc.’s social media

- Have conversations about how you are feeling

- Seek options to connect with others (safe spaces, knowledge sharing)

- Do physical exercise

- Focus on the solutions. A lot is happening around the world and in your neighbourhood.

- Find out more details about Climate Change and what is happening

- Find out what is done and what can be done about it

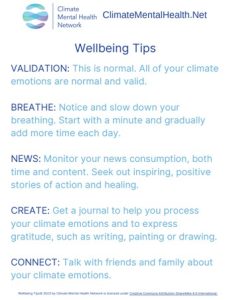

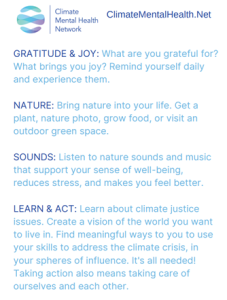

B. The Climate Mental Health Network lists the following well-being tips

C. Climate emotions coping strategies

(Source: Three Climate Emotions Coping Strategies, Climate Mental Health Network)

This resource helps to understand the Three Climate Emotions Coping strategies, which each have a different purpose and are complementary:

- Meaning-focused coping

- Problem-focused coping

- Emotion-focused coping

The Taking Action & Self Care Worksheet (Climate Mental Health Network) helps to explore Climate Actions, interests, skills, and collective action and helps to identify self-care practices (in English and Spanish).

- Climate Emotions Resilience Tips Video (Climate Mental Health Network)

- Affirmations for Climate Emotions (Climate Mental Health Network)

- Good Grief – 10 Steps

D. Positive climate news

- The good news about climate change (WWF)

- A Positive Climate (Podcast)

- Four good news climate stories from 2023 (The Conversation)

- Good News (The Daily Climate)

- Not all doom and gloom: Here are 16 positive environmental stories from 2023 (Vancouver Sun)

- Good news! 30 positive environmental stories from 2023 (One Tree Planted)

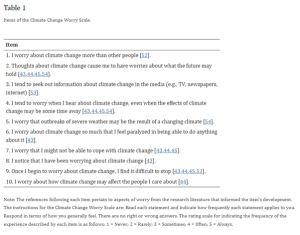

Tools to understand emotional responses to climate change – climate change worry scale

(Source: Psychometric Properties of the Climate Change Worry Scale)

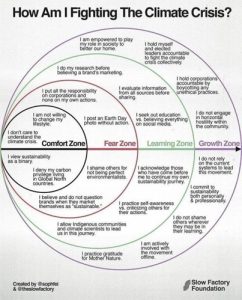

How am I fighting the climate crisis?

(Source: Slow Factory Foundation)

Video Webinar:

Climate Psychology Webinar Climate Justice Union

Tools for Climate Grief & Anxiety: Coping with the Emotional Impacts of Climate Change (University of Calgary)

Dealing with Climate Anxiety, tips, tools and resources – Climate Council

G. Find out more

- Ted Talk: How to turn climate anxiety into action (Renee Lertzman)

- Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as a buffer (S. Schwartz et al. 2022)

- Building resilience to the mental health impacts of climate change in rural Australia (Prevention Web)

4. The role of community organisations when engaging staff and community in climate change and climate justice discussions and work

Providing spaces for your staff for a safer engagement with climate change and climate justice.

“If we don’t act with love towards ourselves and others in our work, we can’t bring more love to the systems causing climate injustice”.

Charlie Wood (Commons Library)

Step 1. Understand the psychosocial hazards of engaging staff members in climate change work

Community Service Organisations need to be aware of their responsibility to prevent psycho-social hazards to their staff members when engaging them in climate justice work.

Safe Work Australia states that employers should minimise psychosocial risk so far as is responsibly practical: “A person conducting a business or undertaking (PCBU) must eliminate psychosocial risks, or if that is not reasonably practicable, minimise them so far as is reasonably practicable.” (Source: Safe Work Australia)

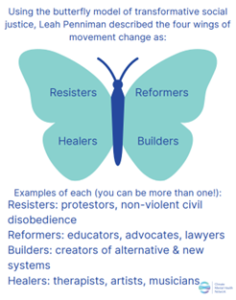

Step 2. Identify climate justice leaders and actors in your organisation

In addressing the emotional dimensions of the climate crisis, it is essential to consider agency, graded exposure, and responsibility. This involves determining who within your organisation possesses the emotional capacity and interpersonal skills to effectively share information about climate change in a safe and appropriate manner while regularly checking in with individuals to ensure their well-being. One approach to managing emotional responses is the scale of personal involvement in climate justice and climate change work, which serves as a self-assessment tool to gauge one’s level of engagement and emotional investment in climate-related work. Implementing tools such as the Climate Change Worry Scale can further assist in quantifying and addressing concerns, allowing organisations to identify and empower individuals to effectively and safely participate in climate justice and climate justice discourse and work within your organisation.

Step 3. Co-develop and endorse a climate emotions safety procedure for your organisations

Collaborate with the team members in your organisations to develop and endorse a Climate Emotions Safety Procedure. This procedure will provide guidance on how to navigate and address emotions related to climate change discussions, ensuring a supportive and respectful environment and processes for all team members. Reach out to Climate Emotions experts to get advice.

Safe Work Australia has published a Code of Practise for managing Psychosocial Hazards at work: model_code_of_practice_-_managing_psychosocial_hazards_at_work.pdf (safeworkaustralia.gov.au)

Climate anxiety would come under the category of Job Demands (high emotional demands) and Traumatic Material. If a workplace is engaging its workers in climate-related discussions or activities, risk management strategies should be used. Since climate work is inherently risky and these risks cannot be eliminated, care should be taken to reduce risks in as many ways as possible. It is NOT sufficient to merely give people the phone number for an EAP. Other risk management strategies must be used in addition to this. For example:

- Give workers thorough training in climate coping prior to engaging them in this type of work.

- Train supervisors, managers and leaders on responding to trauma and where they can get assistance

- Set up debriefing groups where collective care can be practised, with guidelines and training on how to do this correctly.

- Minimise the amount of traumatic materials or events each worker is exposed to (e.g. rotate workers through different roles to provide periods of respite).

- Increase breaks and recovery time after exposure to a traumatic event, such as working with people impacted by bushfires or flooding.

- Empower workers to be able to reduce the psychosocial hazards of the work in other ways – for example, allow them flexible working hours and the ability to work on other allocated tasks whenever they would like to so that they can take regular breaks from thinking about climate change and focus on less distressing tasks when necessary, without asking permission.

- Provide break areas where workers can go to reflect and self-soothe, with appropriate supports and tools for their use (for example, the tools in the section above, journals, mindfulness tools, etc.)

- Ensure that, when climate-related work is allocated, it is clear to the worker what the expectation is around this work and how it aligns with their role to minimise other psychosocial risks that may be attached to the role.

- Have easy access available to well-being officers, spiritual care practitioners, or an employee assistance program.

Step 4. Set up a climate emotions or collective supervision group

Get professional support in setting up a Climate Emotions or Collective Supervision Group or refer staff members engaged in climate justice and Climate Change work to relevant groups.

- Group therapy helps scientists cope with challenging ‘climate emotions’ (The Conversation)

Step 5. Develop community climate emotions programs

To help address climate-related anxiety and mental health issues, it is important to support the development of Community Climate Emotions programs tailored to the needs of the community.

This involves actively involving community members and people with lived experiences with the support of a professional Lived Experience Coordinator, acknowledging the unique challenges and emotions they face. Through meaningful engagement, it becomes possible to identify the specific types of Climate Emotion support that individuals and the community want and need. This might include access to mental health resources, peer support networks, or community-based resilience-building activities. By centring the voices and experiences of those most affected by climate change, communities can develop more effective and inclusive programs that address the diverse emotional impacts of environmental challenges.

- Visit the Processes of Lived Experience Engagement section to be developed by Lived Experience Advisory Group

5. Collective care – learning from a youth case study

The authors of The Care Manifesto describe care as the ability to provide the emotional, social, material and political conditions for individual and collective survival.

Case Study: Learning collective care to support young climate justice advocates

This case study provides an example of collective care among young people. People can reduce their climate distress and feel more effective by getting involved in activism, which also helps climate movements. Young people engaged in activism, however, often face exclusion from adult-led groups and encounter various risks when they do participate. This study uses multiple care theories to explore how adults and young people can work together to create safer and more supportive climate justice movements. In Western Australia, a youth climate justice training program helped 13 young and three adult co-researchers learn and apply collective care. The program allowed young participants to engage with their climate emotions, identify care practices, and map support networks. The study also developed three practices for adult-led movements: active solidarity to address intersectionality, child safeguarding, and building supportive community coalitions. The conclusion is that collective care can help create more just and supportive climate movements for all involved.

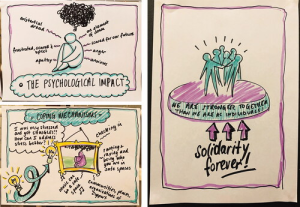

(Visual scribing by Samanta Conner from the youth systemic advocacy and well-being training program 2022. Top left: Young people’s emotional responses to climate change. Bottom left: Ways of coping with climate-related emotions. Right: Collective action is supported by solidarity. Source: Learning collective care to support young climate justice advocates)

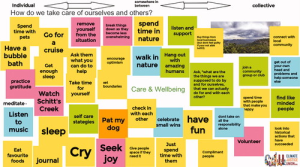

Ways of caring in response to climate emotions range from individual to collective. Group brainstorming from the Youth Systemic Advocacy and Well-being Training Program 2022. Source: Learning collective care to support young climate justice advocates)

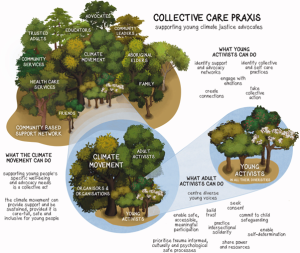

A conceptual illustration of our collective care praxis using the visual metaphor of a healthy forest, made stronger with diverse species and a multi-layered canopy that makes space for new growth. Illustration by Sarah Davies and Kylie Wrigley. Source: Learning collective care to support young climate justice advocates)

Research Findings:

- Collective care benefits not only young participants but also marginalised communities and ecological systems.

- Opportunities exist to enhance intersectional solidarity among activists and educators for trauma-informed, culturally, and psychologically safe movements.

- Centre young people’s voices share decision-making power and resources to dismantle inequities.

- Young people provide critical insights and agency beneficial to the climate movement.

- Adult climate organisers can significantly support young people’s multi-layered networks.

- Adults have a duty of care towards young activists to ensure their efficacy and well-being.

- Lack of safe and supportive movements may cause young activists to disengage and experience increased climate distress.

- Adults should support youth activism in mutually beneficial and empowering ways.

- Collective care praxis can transform climate movements into more caring and just spaces.

- Participatory action research (PAR) is essential and currently scarce in youth climate activism literature.

6. List of training resources

- Psychology for a Safe Climate provides webinar and networking series to become a Climate Aware Practitioner

- The Climate Psychology website lists elements that form the basis of a Climate Aware Therapist.

- The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists offers a webinar series on Climate change and mental health.

7. List of climate emotions support agencies

The Climate Council has compiled some resources that can provide support for people who are experiencing climate-induced mental health impacts.

List of climate emotions support agencies

Community Service Organisations can use this resource to share with staff, train staff, share information with the community and refer people.

For urgent, immediate help, phone Beyond Blue at 1300 22 4636 or Lifeline at 13 11 14. You can also connect with Contact Beyond Blue here. To arrange an appointment with a psychologist, ask your GP for a referral.

8. Case study: Building Resilience to the Mental Health Impacts of Climate Change in Rural Australia

Building resilience to the mental health impacts of climate change in rural Australia

This paper shares findings from a study that used online workshops to gather information from rural Australians. The study looked at what participants thought were effective ways to build resilience to the mental health impacts of climate change and what elements are necessary for successful community resilience-building.

Findings

Participants mentioned many activities, programs, and initiatives they believed helped build resilience. They highlighted the need for three types of community actions:

- General community-led support.

- Community-focused climate action, including inclusive and democratic planning for resilience and adaptation.

- Collective politically-focused climate action.

Participants explained that community-led collective action and planning strengthen social bonds and create a sense of belonging, which increases informal social connections. This, in turn, helps address the mental health and well-being impacts of climate change and supports communities in preparing for these impacts.

The study suggests that strategies to reduce the mental health and well-being risks from climate change might be more effective if they focus on community-led actions that build strong community networks rather than just individual health measures.

Read more

The Commons Social Change Library (Commons Library) have curated a list of Resources to Cope With Climate Anxiety and Grief:

- We Need a Climate Movement that Addresses the Trauma of Fighting for a Burning Planet (Charlie Wood)

- There’s No Place for Burnout in a Burning World (Charlie Wood)

- Healing Our Climate Grief (Sustaining All Life)

- Coping with Climate Change Distress (Australian Conservation Foundation, Australian Psychological Society, Climate Reality Project Australia, Psychology for a Safe Climate)

- Climactic Podcasts On Climate Grief and Resilience (Climactic)

- Handbook of Climate Psychology (Climate Psychology Alliance)

- Catastrophe or transformation? Climate psychology podcasts (Climate Psychology Alliance)

- The Climate Change Empowerment Handbook (Australian Psychological Society)

- Staying Engaged in the Climate & Bushfire Crisis (Psychology for a Safe Climate)

- Emotional Health and Our Response to a Changing Climate (Bronwyn Gresham)

Further resources

- Climate Wellbeing Resources Kit (UBC Climate Hub)

- Strategies for supporting the mental health of infants and children after a disaster: Play and creative expression (Emerging Minds)

- Australian Psychological Society – involvement in environmental and climate change advocacy

- Psychometric Properties of the Climate Change Worry Scale (Alan E. Steward, 2021)

- I’m worried about the environment (Kids Helpline)

- Why mental health is a priority for action on climate change (WHO)

- SURVEY RESULTS: NATIONAL STUDY OF THE IMPACT OF CLIMATE-FUELLED DISASTERS ON THE MENTAL HEALTH OF AUSTRALIANS

- Is the Concept of Solastalgia Meaningful to Pacific Communities Experiencing Mental Health Distress Due to Climate Change? An Initial Exploration (T. Tupou, et. al 2023)

- Is climate grief something new? (American Psychological Association)

- Health and Climate Activism

- 10 Tips for how the Climate Movement can Improve Experiences for Activists with Diverse Health Needs

- Climate Activism Coping Strategies: 5 Tips for Mental and Physical Health

- The Impact of Climate Activism on Health: Exploring Positive and Negative Effects